Call (803) 754-7577

We, the Bee-people: Honey Bees in America

Honey bees are United States immigrants. They are relatively recent newcomers (on the species movement timescale anyway), arriving at the time of colonization sometime in the 17th century. Some are presumed to have made the trans-Atlantic journey as hitchhikers and stowaways; others were brought here purposefully under the provision of their European guardians. ‘White man’s flies’, the Native Indians called them.

An artist’s depiction of the early Cretaceous

Honey bees had already existed for millennia by this stage, and become tightly intertwined with the human experience. The first of their kind appeared in the evolutionary chain some 130 million years ago, when dinosaurs still roamed and huge conifer forests covered the land, evolving in a spiraling symbiosis with flowering plants. Survivors of the mass extinction event that extinguished 50% of life, bees expanded south to Europe and then Africa as the earth warmed during the Pleistocene. By the time humans stopped their knuckle-scraping to stand upright, the insects were already highly sophisticated social organisms. Early civilizations were fascinated by them, forging cultural ritual and spiritual custom about their sweet ambrosial nectar, from Egypt to Arabia to China to Persia.

That’s not to say that the New World was bee-less. Although the honey bee is the most iconic and commercially ‘useful’ of the Apidae family, there are in fact over 20,000 species – many of which are not yellow furred, but iridescent, or monochrome, or even blue (check out the spotted neon cuckoo bee of eastern Australia). Pre-colonial America was home territory to stingless bees, and – though they have suffered huge losses as a result of introduced

Tetragonisca angustula – a stingless bee

competition, habitat loss, disease and pesticides – many are still buzzing about today. You’d be of a luck to spot them often however. Unlike honey bees, these insects are typically not organized into complex social structures, but are of the solitary and ground-nesting sort.

According to records kept at the time, it was most likely the Colony of Virginia which first saw bees make berth, sometime in 1622. Ten years later, shipments were sent off to Massachusetts, though it’s unknown how many of the colonies survived. Similar voyages are believed to have been made around the same time to New York, Pennsylvania, Carolina and Georgia. Whatever the route, and however the means, by the 1680s the honey bee was found almost all throughout the eastern seaboard.

150 years would pass before the honey bee saw the west. Passage through the interior was a perilous gauntlet of rocky outcrops and steep mountains, and any valiant bee traffickers would have their cargo succumb before they reached the other side. Land expeditions were eventually abandoned, and the first bees to arrive were via ship, making a stop-off at Panama, crossing the Isthmus, and finally making land at California. The furry settlers would swiftly fan outwards to neighboring states, whether by natural swarms or wayfarers’ keep.

The revolutionary Langstroth hive

Long years went by, with apiculture little more than a sweet sweet hobby for those who could afford the time – mostly rich estate owners or those of the Christian religious order. It was only in the 19th century that beekeeping came into itself as a moneymaker, and enabling the few dollops of honey scattered about the states to transform into rich, viscous rivers that poured into the homes and porridge bowls of all. Along with better roads for enhanced trade, the honey revolution was largely thanks to three inventions: the movable frame hive, the honey extractor and the comb foundation maker.

The movable frame hive was perhaps the most seminal. Developed in 1852 by the Reverend Langstroth – a congregational minister from Pennsylvania – it was designed around the notion of ‘bee space’ – the gap in-between combs through which bees are able to comfortably make passage. Before this technology came into use, honey collection was a downright monstrous ritual. Swarms would be captured each spring, and developed over the season into colonies in straw, box or clay hives. Come autumn, massacres would take place across the state, as farmers burned sulfur at the hive entrance to kill the colony for the safe requisition of comb. Langstroth’s hive saved the honey bee this continuing fate, and saved beekeepers too from having to start each year from scratch.

Track forward five years, and this time it was comb foundation that was making waves. With its hexagonal lattice, it gave bees a ready-made template for the exhaustive work of wax building, freeing workers to devote a greater share of their energy to raising brood and producing honey. In 1865, the honey extractor came along – a machine that flings out honey by centrifugal force from honeycomb, while preserving the structure – making for another milestone in beekeeper management.

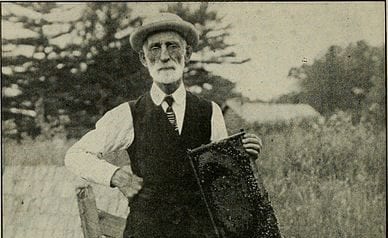

‘Father of Beekeeping’ Moses Quinby

New York State’s Moses Quinby was the first to rear bees entirely for a livelihood. Along with Langstroth and the Prussian-born Rev. Dr. John Dzierzon, he became the American father of the trade, eager to share its secrets and propagate its bounty. Frustrated there was “no sufficient guide for the inexperienced” and concerned about the plague of moths that had seen a certain Mr. Weeks lose “his entire stock three times in twenty-five years,” Quinby published Mysteries of Beekeeping Explained in 1918. He also was one of the first to recognize the superior quality of the Italian queen bee (Apis mellifera ligustica), which became a popular imported substitute to the then common European honey bee (Apis mellifera mellifera).

Not long after the end of the Great War however, foreign trade of bees jammed. Fretful after seeing the devastation inflicted by the tracheal mite across Europe, Congress passed the Honey Bee Restriction Act in 1922, which whacked a ban on almost all imports of honey bees from abroad. Sixty years later, the mite snuck across the border anyway, and – along with the dreaded varroa mite – wrought devastation on American soil. It was only in 2004 that the Act was slightly rescinded.

Over the 20th century and up ’til today, the beekeeping industry has seen tremendous growth. At last count, US beekeepers harvest honey from around 2.59 million colonies. It’s not only the sweet stuff that’s lucrative either – bees have other goods and services to share. Millions make the journey each spring on the back of huge semi-trucks, crossing state lines to pollinate crops ranging from avocado trees to peach blossom trees to squash. Annually, this pollination service is worth between $10-$15 billion to the US economy. Bee wax is used in cosmetics, candles, and to spruce up automobiles, and the nutrient-rich excretion otherwise known as royal jelly is touted by naturopaths as a panacea for a range of maladies and ailments. Since the 90s, DARPA has funded research into whether bees can be recruited to fight terrorism through the detection of land mines.

Though their research and commercial value seems to grow every year, all is not well in the honey bee world. Along with pretty much the rest of the biosphere, the 21st century has not been a friend. It was in 2006 that beekeepers began to notice the die-offs. Since termed colony collapse disorder, the mysterious scourge wiped out up to 40% of colonies over consecutive seasons, causing widespread panic within the industry. Scientists have yet to fully determine the cause of CCD, but the varroa mite is the thought to be the biggest culprit. In a 2015-2016 survey conducted by the Bee Informed Partnership, with funding from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, the total loss of colonies was a brutal 44.1%, up 3.5% from the previous year. In both years, alarmingly, bees perished in the summer – their season of optimum health – as well as the winter.

A grove of almond trees

Will the honey bee become extinct? Despite the hyperbole of crisis-mongering headlines, the reasonable answer is: probably not. Unlike other members of the Apidae family (like the rusty patched bumble bee, added to the endangered species list late last year), humans simply make too much money off their fuzzy backs to countenance such a future. Instead, the spate of new threats and challenges are more problems for beekeepers, who must confront greater financial and management pressures to sustain the same number of colonies.

“It’s really important to understand that the actual number of bee colonies…has remained constant,” University of Maryland teacher Dennis vanEngelsdorp tells the Washington Post. “Yes, bees are dying every year, but you have to distinguish between losses and declines. What’s happening is it’s becoming more expensive to maintain current levels.”

The risk, then, is more an economic one than an imminent ecological one. Higher beekeeping costs are transferred to farmers who use pollination services, and to us, the consumers of bee products. Since 2006, the shelf price of honey has doubled. Some beekeepers have been pushed out of business in the struggle to make ends meet, and the collective hardship has initiated a major shift. In a short space of time, we have seen the industry go from one which was mainly local to one which is predominantly export based. 350 of the 400 million pounds of honey that we spread on our morning toast, trickle on our pancakes, and soak into our pies is produced outside the country.

Honey bees are foreigners that have taken over the American continent – to our great and lasting benefit. Though we don’t share as much of a history with them as other cultures about the world, they have merged into the American imaginary, lifestyle, science and economy to make us better in our laboratories, our stock markets, our pharmacies and our desserts. Our thrumming worker/companions are not invulnerable however. We, the bee-people, must be the caretakers they deserve.

Words by Kate Prendergast

Leave a comment